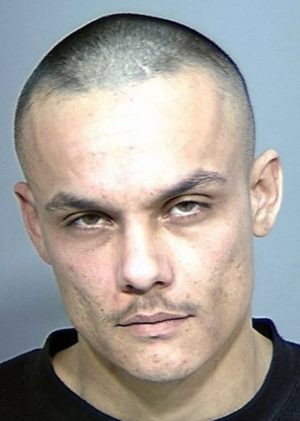

My Buddy Tito, The Violent Criminal Actor

Nathan Wagar

When I was a teenager and in the system, I was sent from southern up to northern California to live, and I had a friend named Tito. Well, actually his name was Alvaro, but we all knew him as Tito. I got along great with his friend Michael, and I even was invited to his girlfriend’s quinceañera. Michael and I used to sit at the park and listen to him rap the lyrics of the latest Brotha Lynch Hung album. We never bothered telling him that he was terrible, although Michael had this theory that Mexicans couldn’t rap on the beat properly because of their accents.

Tito was occasionally a smartass and was never very good with his fists, which was a bad combination where we lived. He dropped out of school later, but we still hung out because we lived by each other, and he started having some issues with ice, but a lot of people did out there. He was still the guy that paid for my coconut popsicle when it was blazing hot out, the paletero came by and I didn’t have any money. He cared for his girl, he cared for his friends, and he cared for his dog.

In 2008, Tito and his brother shot a man 13 times, one of which was in the head at close range.

It happened behind the same abandoned house that had been on the street corner for a couple decades at least, scrawled with gang graffiti and serving as a sometime home to the drunk of the week. There was a party going on nearby, and apparently Tito updated his typical strategy from losing a fight, to luring the guy out back to get shot instead. Tito was a great guy, he just had a quirk where he was willing to kill for a street gang.1)Sabra Stafford, “Jury Convicts Turlock Brothers of Killing Rapper,” Turlock Journal, April 5, 2011, www.turlockjournal.com/archives/8869 (accessed March 1, 2017). My friend Tito was a violent criminal actor.

The point of the above story is that for the vast majority of his life, Tito was an ordinary guy. He had his ups and downs, but given a very narrow set of situational criteria he would kill someone. To this day, his mother refuses to believe the killing was gang related. This sounds like the story that memes are made of, along the lines of “My baby didn’t do nothing.” To be sure some mothers are in denial, but a great many of them really never see that side of their boy. How could she? He only killed when colors and numbers were involved, and colors were never a part of her world. The Tito that she knew quite rightly would never do such a thing.

To understand the term violent criminal actor, it is helpful to look back at where it comes from. It is actually a somewhat obscure term that is seldom used in criminology, and originated with a criminologist named Lonnie Athens. Athens talked about the creation of a VCA through a process he called “violentization.” Lonnie’s ideas stemmed from symbolic interactionism, which is controversial due to its foundations in pragmatism and believing that reality doesn’t exist objectively outside of the “actor.”

Rather, reality is constructed through the actor’s own interpretation of his connections with the environment and other actors. It could be summarized as reality by subjective connectionism.2)Lonnie Athens, Violent Criminal Acts and Actors: A Symbolic Interactionist Study (New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980). However controversial the underlying philosophy may be, the model that Athens used fits well with environmental criminology, which sees the criminal act as an event of certain elements converging in time and space, that can only take place under certain conditions.

No person makes decisions or finds meaning in a vacuum. We develop cognitive templates for our experiences and what has worked for us in our decision making processes according to our moral allowances, and these templates have a set of criteria that take on the form of a cognitive script.3)Per-Olof Wikström, “Situational Action Theory,” In Encyclopaedia of Criminological Theory, edited by Francis Cullen and Pamela Wilcox (Beverly Hills: Sage, 2006).

When certain criteria are met, the script is triggered, along with its corresponding decision options. A VCA is a person that has a varying level of violence that he is prepared to use as a potential solution for certain scripts. He essentially becomes a violent “actor” in this situational script, and the fact that the violence may be criminal makes him a violent criminal actor.

Perhaps even more importantly, the VCA acts in reaction to the other agent, much like a chess game. The chess game only continues provided that the other agent fulfills the criteria for the game to exist as a cognitive schema in which to take action on. If the other player starts doing something that doesn’t look like chess as the VCA interprets chess, then they are no longer interacting in a violent criminal context, and so the violence doesn’t happen.

A combat veteran is a violent actor, except his violence is conditioned and “triggered” by a script that includes a role as a soldier, a mission, an escalation of force, and a threat within the proper context. It still takes a process of violentization, as Athens discusses, in the form of training and context for him to perform a violent act.

This part is important: He is no longer a violent actor until those criteria are met again, because that is the context in which he interprets violence as a proper decision making response. If, during a battle, the threat were to drop his gun and hold his hands up in surrender, the conditions and therefore script for violent action would no longer be present, and so the soldier as a violent actor would not fire. If he did, ironically at that moment he would become a VCA, in violation of the Geneva Convention.4)Richard Rhodes, Why They Kill: The Discoveries of a Maverick Criminologist (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 286-312.

My friend Tito was a VCA in very specific contexts, and outside of those contexts he would be somebody you would invite to a barbecue (just not the one where he killed the guy). Many people have dealt with aggressive situations and found a level of violence that they are comfortable with in accordance with their morals, and will not go further unless their cognitive schema is highly altered with a new experience.

Even the top percentage of predators such as serial killers and those that commit sex crimes have a set of criteria that must be met to even target someone, let alone follow the act to completion. A woman may trigger the script to be targeted and followed home, only to have the script aborted when the husband comes to the door to greet her. This doesn’t fit the script, and so the movie scene ends.

This is something that many people in the protection industry will never understand; that the boogeyman is you, in the right circumstances and given a certain set of moral beliefs. This is understandable, since most civilians’ cognitive schemata of violence are cobbled together from second and third-hand testimony, media, and what they imagine it would be like and how they would respond in their own heads.5)Strategies used by the VCA to adapt to changing conditions in order to continue the script is dependent on experience, and needn’t be discussed here. The original point still stands.

The violent criminal as many people think of one doesn’t exist, they simply have an expanded tool set for their goals. A VCA is really a larger decision making matrix combined with a triggering template formed by that particular person’s experiences; it is not a “superpredator.” Does this make their goals or the decision options moral as we understand the word? Absolutely not. But these safe distinctions that define the boogeyman don’t apply well in the real world, and this was something that Athens found out in his research.

I have had many people and instructors stand right next to me and without irony speak of preparing for violent criminal actors, and not realize that in my past, from the ages of 10-17, I was one myself. I was so much of one that I was put into the National Gang Member Database, and it was very difficult to get into the military. I’m not anymore, but that’s because I am not committing crimes anymore. If that surprises you, then you have the wrong understanding of what a VCA is.

Even law enforcement frequently can fall prey to a negativity bias, since they see the bottom percentage of actions by the lower totem poles of moral humanity as a large chunk of their day. They don’t live with these people, go to Mass with them, go to their weddings, or share food with them. Those that work in the correctional field may work around prisoners, but predators locked around other predators do not behave as they normally do on the outside either. This results in a skewed sample of law enforcement experiences that end up being formed into their own schema of violence, that may not be accurate to reality.

This should give us hope, however. Rather than spending training time on fascinating but highly theoretical models of criminal psychology, we can focus on our environmental and behavioral threat assessment, avoiding contextual triggers for violent criminal action, and other critical soft skills. Rather than seeing incredibly complex and unknowable people as types of boogeymen to be safely categorized and avoided, we can pay closer attention to the situational boogeyman that just bought our kid the popsicle.

Remember, my friend Tito was a VCA except when he wasn’t, and he wasn’t for 99.99999% of his time on this earth, even now as he serves 80 to life.

References

| ↑1 | Sabra Stafford, “Jury Convicts Turlock Brothers of Killing Rapper,” Turlock Journal, April 5, 2011, www.turlockjournal.com/archives/8869 (accessed March 1, 2017). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lonnie Athens, Violent Criminal Acts and Actors: A Symbolic Interactionist Study (New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980). |

| ↑3 | Per-Olof Wikström, “Situational Action Theory,” In Encyclopaedia of Criminological Theory, edited by Francis Cullen and Pamela Wilcox (Beverly Hills: Sage, 2006). |

| ↑4 | Richard Rhodes, Why They Kill: The Discoveries of a Maverick Criminologist (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 286-312. |

| ↑5 | Strategies used by the VCA to adapt to changing conditions in order to continue the script is dependent on experience, and needn’t be discussed here. The original point still stands. |

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar