The Hood is Not Coming to Get You

Nathan Wagar

As current events become increasingly violent across the world, there tends to be a corresponding fear in city populations of the “savages taking over.” In the more extreme versions of this fear, the criminals and poor will go to the suburbs and riot, loot, rob, rape, and kill. After all, predatory crime often targets resources and there aren’t too many resources in the ghetto.

In the less extreme variations of this misconception, reality-based self defense instructors preach constant awareness regardless of location, because “real” violence is sudden and can strike at any time and place. The only antidote to such unexpected violence, it is reasoned, is constant awareness.

Now this is an extreme fear, but like all fears there are kernels of truth that lie within. Tragedies such as the flooding of New Orleans and the subsequent violence should leave no one under any illusions that all people are fundamentally altruistic when social structure breaks down. People like Sylville Smith’s sister saying to “burn down their suburbs” during the Milwaukee Riots do not help much in allaying these fears either.1)Anthony Logan, “Cnn’s Edited Footage from Milwaukee Family. Watch the Unedited Version Here” (video), August 16, 2016, accessed May 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-8Cn6boqcA.

However, talk is cheap, and the realm of personal protection lies in the reality of actions. The facts of violent crime are a bit different than the fear, or even intent to commit violence.

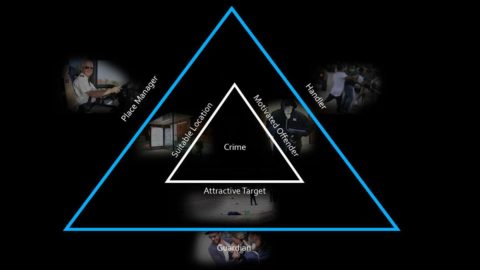

Just because I want to hurt someone doesn’t mean I can or will; certain factors have to be in place for any criminal event to happen, let alone violence committed by a certain population against another. So let’s take a look at a common myth and show how the kernel of truth has become distorted.

“Criminals target the nice neighborhoods because that’s where the high value targets are. They don’t want to commit crime in their own neighborhood because that’s how you get caught.”

Reality: It is a fact that people travel different distances to commit different predatory crime types. However, most of these distances are quite short, particularly for violent crime.2)A. Rand, (1986). “Mobility triangles,” In Metropolitan Crime Patterns, ed. R. M. Figlio, S. Hakim and G. F. Rengert (New York: Criminal Justice Press, 1986), 117-126. For the most part there is only a very short buffer of avoidance from their own home to avoid recognition, and the vast majority of criminals work within and target their own neighborhoods. There are several reasons for this, here are merely a few:

(A) You have to know where the game are to hunt

Criminals typically learn about targets of opportunity through the course of their day to day activities such as work, school, or hanging out in the neighborhood, or through their social network. Burglars may pass on hot tips, a man may see that nobody locks the side window of their store as he steps outside for his smoke break, or a boy may be hanging out at his friend’s house and see that the neighbor has rims on his car.

The issue is that most people’s activities take place in their own neighborhood, and most of their friends live in these neighborhoods as well. Their whole world is a self contained society on that far side of the freeway, and unless they not only have a friend in another neighborhood, but have that friend’s knowledge of that other neighborhood’s opportunities, they simply don’t have any awareness of the location or suitability of potential targets.3)P.J. Brantingham and P.L. Brantingham, “Environment, Routine and Situation: Toward a Pattern Theory of Crime,” In Routine Activity and Rational Choice, ed. R. V. G. Clarke and Marcus Felson (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1993) 259-294. The alternative is to actually go driving in a nicer neighborhood, which brings its own problems as we will see next.

(B) Gas costs money

This may sound flippant, but it can be very easy to forget, or not even realize, the realities of being poor. Driving around in a vehicle may seem like a leisurely activity to some, but for others a vehicle is a necessity, and someone’s “reach” in the city is very much dependent on how many people in the car can chip in on fuel.

No gas means no go, which leaves public transportation and its own differing problems. Now add to the fact that they are not going from point A to point B but actually have to locate and monitor potential target opportunities, and the issue gets more complicated.

(C) Baseline

Now we come to a point that is a bit ironic. Many people point out that a criminal would not want to victimize their own neighborhood because they will get recognized, but an actual criminal is thinking he is less likely to get caught in his own neighborhood because everybody looks like him, whether ethnically or the same class.

Cops and other people immediately notice different races and socioeconomic demographics, and if someone doesn’t fit the baseline it invites further questioning. Feeling like a fish out of water can also raise a criminal’s stress levels, leading to further anxiety and odd behavioral cues.

Try reversing it. If you were a white male, for instance, would you want to rob someone in China Town on the basis that people in your part of town would “recognize you?” Or do you think perhaps that you would stand out more in a completely different culture?

Now picture someone from a poor part of town, driving in an upper class neighborhood scanning houses, most likely in a clunker with a possible outstanding warrant for his arrest. Is it really worth it for him to risk getting pulled over or having the neighbors report suspicious activity from a man they don’t recognize?

(D) Cash economy

Criminologists have talked about the CRAVED model (Concealable, Removable, Available, Valuable, Enjoyable, and Disposable), and this is simply an acronym that represents what many crime types such as theft or robbery tend to target when it comes to physical goods. Poor areas of town still survive on cash economies, and in these areas title loan businesses, check cashing locations, pawn shops, laundromats and other such places are readily available.4)Eric Beauregard and Melissa Martineau, “An Application of Craved to the Choice of Victim in Sexual Homicide: A Routine Activity Approach,” Crime Science: An Interdisciplinary Journal 4, no. 24 (1 October 2015): 1, 10.1186/s40163-015-0036-3.

How many times per week did you use cash as opposed to your debit or credit card when making a purchase? Credit cards are able to be canceled and tracked, whereas cash is easily taken, used immediately, difficult to track, and so fits the CRAVED model.

(E) Disadvantage, not disorder

Being poor is a relative thing; if everyone in a group has one dollar, nobody is the poor one. If one person in that group has two dollars, now we have a case of what is referred to as “disadvantage.” In my material I prefer to call this an economic “edge,” or the split in two different baselines of people with one dollar and the person with two.5)Catherine E. Ross, John Mirowsky and Shana Pribesh, “Powerlessness and the Amplification of Threat: Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Mistrust,” American Sociological Review 66, no. 4 (August, 2001): 568-91, accessed May 7, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088923.

If we combine all the above factors, we start to get a clearer picture of predatory dynamics. In one sense, the common adage has some truth that a criminal doesn’t want to get recognized and would prefer higher value targets. If we balance that out with the counteracting problems, we begin to see a situation that corresponds better with reality: A robber leaves a certain distance from his home, targeting people in or near his neighborhood along an economic “edge.”

This could be a person with nice jewelry on the smallest level, a house that is nicer in that same bad neighborhood on another level, or on the larger level the main strip dividing his neighborhood from a nicer neighborhood.

At that edge, a man from his part of town can be in the public setting with members from the far residential area, but if he were to cross too far past the “edge” of the main strip he would begin to stand out.

All of these examples constitute an economic “edge” and so can serve as potential attractors for crime. There are other edges as well, both environmental and behavioral, and I will cover those in future articles.6)Justin Song et al., “Crime On the Edges: Patterns of Crime and Land Use Change,” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 44, no. 1 (September 2015): 1-11, accessed May 7, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/15230406.2015.1089188.

In summary, both people and crime are complex systems. They have patterns, but we need to try to think through what we are attempting to protect ourselves against, because this will help us to prevent from falling into paranoia, and painting entire communities with broad strokes.

Crime is highly concentrated in time and place, and it tends not to travel very far. The edge that you have to worry about probably lives in your own neighborhood, a couple streets down.

References

| ↑1 | Anthony Logan, “Cnn’s Edited Footage from Milwaukee Family. Watch the Unedited Version Here” (video), August 16, 2016, accessed May 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-8Cn6boqcA. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A. Rand, (1986). “Mobility triangles,” In Metropolitan Crime Patterns, ed. R. M. Figlio, S. Hakim and G. F. Rengert (New York: Criminal Justice Press, 1986), 117-126. |

| ↑3 | P.J. Brantingham and P.L. Brantingham, “Environment, Routine and Situation: Toward a Pattern Theory of Crime,” In Routine Activity and Rational Choice, ed. R. V. G. Clarke and Marcus Felson (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1993) 259-294. |

| ↑4 | Eric Beauregard and Melissa Martineau, “An Application of Craved to the Choice of Victim in Sexual Homicide: A Routine Activity Approach,” Crime Science: An Interdisciplinary Journal 4, no. 24 (1 October 2015): 1, 10.1186/s40163-015-0036-3. |

| ↑5 | Catherine E. Ross, John Mirowsky and Shana Pribesh, “Powerlessness and the Amplification of Threat: Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Mistrust,” American Sociological Review 66, no. 4 (August, 2001): 568-91, accessed May 7, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088923. |

| ↑6 | Justin Song et al., “Crime On the Edges: Patterns of Crime and Land Use Change,” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 44, no. 1 (September 2015): 1-11, accessed May 7, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/15230406.2015.1089188. |

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar