How to Read Graffiti: The Street Hotline

Nathan Wagar

Most of personal protection involves being able to navigate safely through urban environments. Quite simply, the violence happens where the people are. Understanding the rhythms and flows of the city, as well as the social networks and hierarchies within, are critical to stacking the deck in your favor so that violence never gets the chance to happen.

In built architecture there is the concept of objective use, in contrast to subjective. Objective aspects of a building are generally what the architect had in mind when building the structure. A protestant church, for instance, would not serve well as a Catholic parish building because there is no raised altar structure for the Mass to take place.

A protestant building has a focus on the podium, because the theological focus of the service is the sermon, rather than the sacrifice. In this case, there is an intended purpose built into the structure itself, and this would help guide the appropriate use of the building.

Now to the dismay of many architects, there is a reciprocal nature of human behavior guiding building intentions which in turn guide behavior, and people do not always use a building for the intended purpose. That same intended protestant worship building can be taken by a Catholic community and have an altar jury-rigged out of a table and a cover, the same as a former retail store building can be turned into a restaurant.

In these cases, the subjective uses and behavior of the people within the building are the more immediate, if not necessarily the most appropriate concerns that we need to be aware of when reading an environment.

This is not to say that knowing the objective meaning of an environment is not important; it is. We need to have an understanding of all baselines before we can spot anomalies along the “edges” of different systems. A split between the objective and subjective use of a building, for instance, can cause us to dig a little deeper to find out if that split is appropriate or not.

Whenever we are in a new environment, there are objective aspects, as well as subjective, just as with buildings on the micro scale. If I were in Juarez in Mexico, for instance, there is a certain expected norm that goes along with the laws and “official” culture of the State. But that very rarely is what will affect me. We can think of the “official” lay of the land as an objective, static system. This is what we would learn on the brochure.

How is a residential street normally supposed to be? Well, there will be people living in houses, children playing on the street, and traffic flow as people and children go into and out of their homes for work and school. That’s the static purpose of a neighborhood.

But this tells you almost nothing about the real time, or dynamic system, of what is going to happen in the neighborhood as you are there. I would argue that the nicer, or more socially ordered a neighborhood is, the more it will resemble the brochure. We don’t need to know much else other than what the norm is and conduct ourselves accordingly.

In socially disordered neighborhoods, however, the entire problem is that the brochure isn’t working anymore. There is drama in the streets, the windows are closed and barred, and nobody is talking about what’s going on, especially not to an outsider. How do we read this?

Graffiti

Graffiti has long been called the “street’s newspaper,” and for good reason. Where the “brochure” breaks down, subcultures tend to supplement a failed State with their own forms of communication, and reading these forms of communication gives you a better understanding of the subjective, and therefore more immediately relevant lay of the land.

This has not been lost on the State, indeed in South American countries it is not uncommon for the State to have fake revolutionary graffiti drawn to indicate skewed levels of popular support for the regime.

Graffiti is transient, and can be changed quickly. This is important, because it gives us more immediate information about social situations than the neighborhood street buildings ever could, and it will communicate to us even if there is nobody present to say anything to us directly.

There are many nuances on the local level of different gangs, groups, and styles of graffiti, and it is very easy to go down a rabbit hole on this fascinating topic. What I want to present for you here are some generic concepts that will apply across the board internationally, regardless of where you are and whether you are familiar with the culture.

Legibility = Purpose

There are several types of graffiti and many different ways that scholars classify the different types, ranging from tagging to gang graffiti to political, and the different subdivisions within each. All of this is important and interesting, but our focus for right now is the fact that the different types of graffiti follow a continuum of legibility according to what the graffiti is for.

Certain types of graffiti have certain purposes, and these purposes and types of graffiti reliably correspond to levels of readability. Let’s unpack this a bit.

(A) Typical “What the hell” tags.

On the low end of the legibility scale, we have different forms of tagging. For the purposes of simplicity, I will refer to all artistic graffiti as tagging. Tags are notoriously difficult to read, and range from hastily scrawled to giant pieces of work referred to as “bombs” that you have probably seen at one point or another in empty train stations. Our main concern isn’t so much the terminology, but rather the fact that when we look at the graffiti our first sense is “What the hell does that say?” If it isn’t communicating a clear outward message in word or picture, then the picture itself is the purpose.

If the picture is the purpose, then the next thing we can ask ourselves is how much time was involved in making it. Let’s say we had a giant, artistically drawn tag on a wall. Is it public or private? If it’s public, then it tells us something about the law enforcement presence as well as the social cohesion of the neighbors.

Nobody stepped in to stop it, the police weren’t around to stop it, or they were present during the day but there are juvenile delinquents running around at night. If it isn’t public, then it is probably on the margins of the city, such as abandoned train stations, and this is why even the nicest cities often have tags all over their train cars.

Tags tell us a bit about cohesion and are correlated to certain types of crime, but don’t necessarily indicate violent crime. So if there is a large amount of graffiti that I can’t read in my area, I am either on the margins or there is an element of social disorder, and I should pay attention to other cues.

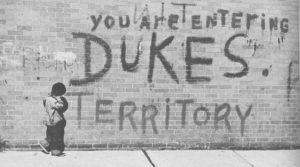

(B) Stylized, but far more legible, this gang graffiti is inter tribal with the standard codes of meaning, and is designed to communicate with other gangs.

The next step in the legibility scale could be gang graffiti. Gang graffiti comes in many forms and symbols, and again it is all important to know and very interesting. What stands out for the reader however, is the fact that gang graffiti is far more legible because of its purpose. Gang graffiti is meant to communicate to the same community but different “tribes.”

The other tribe may not know your different codes and styles, so it is necessary to be more legible. Gangs are not concerned with art necessarily, they are concerned with communicating status and direct messages to other rivals, as well as residents that also may not share their code.

(C) The lack of stylized text makes this crystal clear not just between tribes, but also to the community at large. You as a civilian are not welcome here either. This makes sense when we consider that Italian gangs were integrated strongly with the community, and so messages to the community needed to be clearly understood.

Once legibility is established, the typical symbols and numbers found in gang graffiti are usually enough to immediately distinguish it from tagging, and there is a corresponding change in threat level. Gang graffiti is about immediately pertinent communication for other non-State actors, and so artistic aspects are more of a side issue.

Future attacks, lost loved ones, territory boundaries, and clashes with law enforcement are all communicated largely in real time for the benefit of you, the reader. The broad rule of thumb so far, you may have noticed, is that

The more you can read it, the more you should.

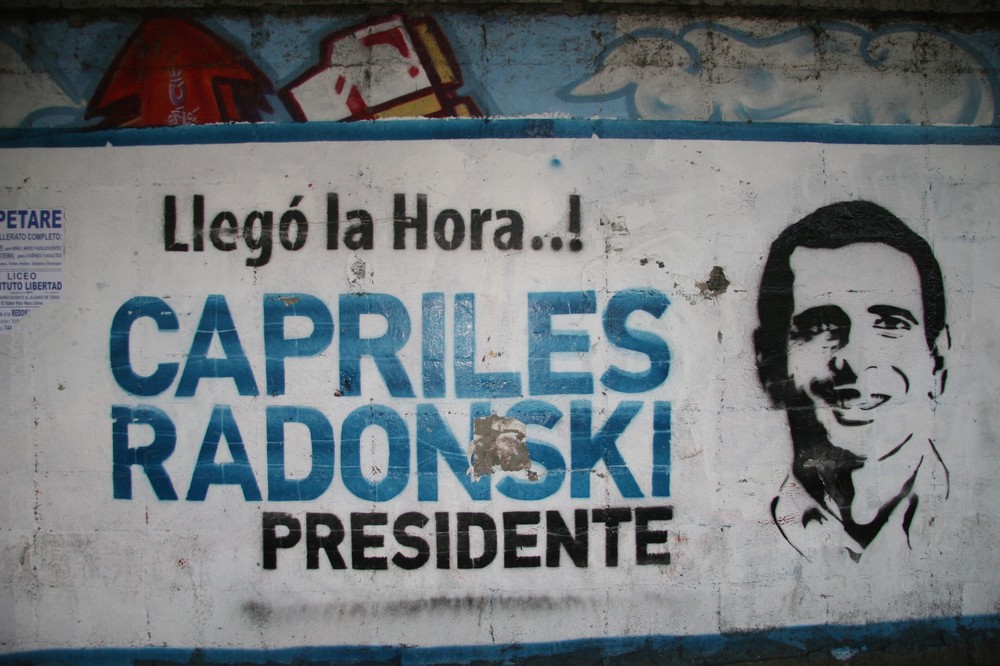

(D) This graffiti is political, stylized, but extremely clear. It obviously took time to make but is also in a public place rather than a marginalized location. This would indicate social disorder in the neighborhood, with the message being to the community primarily, about the State, and only tangentially to the State. The State holds the power, and the graffiti is an outlet.

The most legible of graffiti tends to be political graffiti. Political graffiti is designed to communicate to and about the State, as well as internally within a community. There is yet again a correlation between the artistic aspects and time spent on the piece, and the social climate. There are on average far more intensively designed, mural type pieces in democratic countries than there are South American dictatorships, where the piece is more hastily constructed.

If a mural has cryptic numbers and slogans but revolutionary imagery, by and large the political climate is one in which there is burgeoning community resistance, but they do not pose much of a threat to the government and so no State change is expected.

(E) This is extremely clear political graffiti, designed to communicate messages not just horizontally to the community but also vertically to the State. Change is expected, there is a rival party that has political clout that the community can rally behind. The nature of the conflict can be peaceful or violent, in this case there is no indication of violence. The lines are clean, the mural took time to make, it took place in public, and this indicates at least a semblance of a democratic environment, and indeed that is the process that appears to be described here.

In this kind of environment, it is wise to be wary of taking sides lest you be targeted by either one, but you don’t necessarily have to worry about war breaking out in the streets. Extremely clear political graffiti with pointed messages and few community code references is immediately relevant. It tells you that there is a revolutionary sentiment, that the community sees itself as a rival to the State, and so conflict (whether peaceful or violent) can be expected.

In this case, the message is not galvanizing support so much as demonstrating clearly, to the State, that the support is already present. This need not be seen as a violent revolution, it could be something along the line of a civil rights march, a protest for community chosen law enforcement officials, etc. Context is always king.

Knowing these different aspects of how and why graffiti is written, rather than what it says, not only tells us the lay of the land, but it also tells us what questions to ask when used in combination. It is much like animal tracking, in that sense, in that we are using graffiti to learn about environment, and then in turn how the environment has changed to affect the graffiti.

For instance, what if we had extremely clear political graffiti that was hastily drawn? We could reasonably surmise that there is a strong communal political presence that is parallel to the State, but that the immediate on the ground circumstances prevented the tagger from spending much time on the piece. This could have been law enforcement, or the State in a dictatorship.

In summary, use the different rules of graffiti and think about how combining and contrasting the different rules can tell you about the surrounding environment.

1. The more you can read it, the more you should.

2. The more you can read it, the higher level the message (from tribe to community to State).

3. The more elaborate and labor intensive it is, the more it tells you about the climate.

4. Contrasting and comparing elaborateness and legibility can help you narrow down the context.

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar