Coaching Commandment: Praise Doesn’t Roll Uphill

Nathan Wagar

The single quickest way to kill your own development as a coach is to listen to the praise of people that pay you money. Period.

Coaching can be a thankless job, and this is particularly the case when you are trying to develop new material that can take our knowledge of violence and self-defense a decisive step in the right direction. The market is over-saturated, and trust me I understand the need for positive feedback. The nature of being a coach is that there aren’t as many of us, and so the people that are most likely to give us this positive feedback are of course our clients. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; in one sense the very measure of our success has to be our clients.

But just like with our cognitive process for attaining any sort of truth, there always has to be a verification of the model that we have of ourselves and our own material, and this verification needs to come from as many different directions as possible in order to avoid cognitive biases. Knowledge is an open system, not a closed feedback loop. Life is a complex reality that is constantly shifting and changing even as some static elements remain true. The second you measure it, some of your knowledge is in that very moment obsolete. You have to be open to input and constantly changing, but the key is that the input is always external.

Let me repeat that: The input is always external.

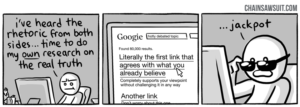

The reason why should not be difficult to see. An instructor-client relationship is an irreducible dynamic, and so forms a circular feedback loop in itself. You cannot expect new, relevant information to come from within that one cognitive loop. If you turn your open-system coaching-development process into a closed system of client feedback flowing to the instructor only to flow right back to the same client, then you are finished. Period. Done. You are irrelevant.

Let’s say you are a self-defense instructor that has a respected background in a pressure-tested style like boxing or Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. A combat sport can’t be transmitted directly into a street system, and so there needs to be modifications to deal with things like weapons and multiples. You use your expertise in the base art to personally construct solutions to these problems, possibly with some willing bodies that also may be clients, and then you teach a grappling or striking-based system for personal protection. Your clients love it, it works great for them, and you troubleshoot based on their feedback in class.

You just failed

Let’s take the above scenario and tease it apart. For one, your expertise in the original combat sport does not necessarily carry over to violence, and so if you have no experience with violence then you don’t know how the two fit together. Perhaps you have a client that was deployed to combat or worked as law enforcement, and you picked his brain and worked with him while developing your material? That is slightly better, your “lens” is a bit more clear, but he has no reference for high level combat sports and how it might apply to his experiences; you are essentially talking past each other.

He would also need to give you feedback based on exposing his newfound knowledge to his own external variables, otherwise his feedback can’t even properly count as feedback. After all, if you rigged the pressure-testing game within your own gym, then how can your new material properly be said to work outside of it?

The problem doesn’t end there. Nothing says that he performed effectively in the violent scenario, if the experience even applies contextually, or if he even remembers the event correctly. That would take further external corroboration based on our knowledge of memory, what other people who were there said or did, and the broader social conversation on our knowledge of violence.

Still another issue is that even though your specialty might be in combat sports, that doesn’t mean that the technique you developed can be performed successfully at a high level within your own area of expertise. Is your defense only supposed to work against people that don’t train? You can’t know, unless you received external feedback from the top down or at the very least horizontally from a peer in your own discipline.

That further leaves a discipline divide, since what works within a grappling context may not work against hard strikes, and vice versa. This means that you need external input from experts in other disciplines; moving not just horizontally but across disciplinary boundaries.

And those external inputs? They need to continue in their own loops. They have to be continuous and ongoing, to help not just test your material’s ability to withstand diverse pressure but also the test of time; to see if it was a fluke or if it can withstand the initial weathering and form a static system of proven knowledge. Coaching never ends, and the second you stop learning, is the second your coaching itself dies. Here are the facts of human experience:

1. You don’t know shit

Not even about the things you actually did. This is not some form of radical skepticism; you are in fact learning about the objective material world, but you have no concept of the sheer significance of your experiences.

The only human knowledge that is worth anything in the broader scheme of things has been shared and picked apart by millenia of human experience in an ever-changing world. Some systems of knowledge are dynamic and always changing with their superficial contexts; others stand the test of time for many people in many contexts and are seen to be true for people as a whole.

Every bit of knowledge is interdisciplinary, and comes through filters that were themselves given to you. Your filter itself needs to be compared with other social filters, so that you can put your own experiences and knowledge in context, and then re-appraise the situation. You have five senses, and no one sense can be judged in isolation. You perceive information through five channels and make judgments not only about the information but also the senses themselves in light of that information. Your knowledge is cyclical, and cannot ever stop. We evolved this way to survive.

Put another away, if you stop learning from as many directions as possible, your material is stupid. This is the case even if you were to form some sort of coalition, organization or collective with multiple experts. There is always a changing world that needs to be adapted to, there is always a knowledge gap between you and another discipline, there is always a knowledge gap between your coalition and another instructor coalition, and so on.

2. You weren’t even designed to know shit

Your cognition is limited, and can’t even know something perfectly within its own limitations. This actually is not a flaw. The entirety of individual knowledge is heuristic; the science of “good enough.” This is a compromise that is necessary given the static-yet-dynamic nature of reality. We are creatures in time, and we don’t have the luxury of ever getting anything down perfectly because the world is already changing.

Put another way, if your material stays the same regardless of the variables it is tested against, your material is stupid.

Notice that the above point assumes that you are, in fact, constantly testing it against new variables, otherwise you have failed before you even get to this point.

3. Society doesn’t even require you to know shit.

Keeping in line with the fact that knowledge is a cost-benefit, “good enough” series of trade-off analyses, the same applies to our social context. Instructors imagine that they give serious consideration to how much our evolution as a species has shaped our strategies of dealing with violence, and yet don’t seem to realize that our knowledge and teaching of violence itself is placed within a social context shaped by evolutionary forces. A striking example can be seen in the phenomenon of social proof.

Once the more pressing threats of getting eaten by lions or getting shot on a street corner are done away with, we move away from being genetically culled from the herd outright. As we become more civilized, the brutal, self-correcting nature of violence is not something the majority of us ever experience, and the few that do experience it run into the points discussed above.

Now our evolutionary cost-benefit analysis changes, as the means of propagating our genes is less directly concerned with avoiding certain death as with being seen as a desirable mate. Social proof is one of the mechanisms to accomplish this, and it can be yet another death trap for an instructor.

The more popular a coach is with the wider public the more status he has, and the more he experiences the benefits of this increased status, the more motivation he has to keep the process rolling along. This can be a benefit for the species’ survival, as demonstrably powerful individuals have proven to be successful at violence, and following them is probably a pretty good idea. It’s also a pretty good idea for the coach to be good at not getting eaten or otherwise killed, so there are powerful external variables that test and refine the material.

In a civilized society, however, asocial variables are no longer an issue, and so all external variables become social. Once pure function is no longer needed, it is necessary to add a bit of flair, because the selectors are clients, not lions or cannibalistic rival tribes.

Before, status was tied directly to effectiveness at violence; you couldn’t get social proof if you sucked at fighting, because you would probably be dead. Being dead doesn’t reel in the hunnies. But in civilized society social proof can be gathered from other means; the community shares the burden and not every man must be adept at violence. Status, then, can be separate from effectiveness, and tied solely to money. This is not to say that it always is, but only that it can be; this ambiguity is actually a major part of the problem.

There is no need to release effective, pressure-tested material because his clients won’t know the difference, and the clients will never know otherwise anyway because they will statistically never find themselves in a violent situation where their material will fail. This is particularly the case with the people that can afford effective self-defense training, as opposed to poor youth at a boxing gym who pay for their training by actually fighting in the ring. In this new social context, having the client “like” the material (as opposed to matter-of-factly accepting its effectiveness), and even liking the coach himself, is just as important if not more so for achieving that social status.

The mechanism has changed from the necessity of teaching self-defense for survival, to the necessity of teaching self-defense as such for social proof. And finally:

4. Your clients sure as hell don’t know shit

They pay you money for a reason: You know and can do things that they can’t. Here is the kicker: They don’t recognize your ability in a way that matters for your development, even if the lens gets a little more “clear” if they have similar experiences, or similar training, etc. All they can judge is what they think you can offer them in what they think they are deficient in. In other words, they aren’t even in a position to judge if you are full of crap, so their opinions about your awesomeness need to be continually re-contextualized against your other feedback loops.

That phenomenon of social proof is especially dangerous in this case. The potential client that is looking to learn self-defense may recognize his ignorance and turn to popular opinion for an effective martial art, since in the client’s mind popularity and effectiveness are most likely to be linked. He looks to social proof to choose an instructor, this in turn provides positive feedback to the instructor to continue what he is doing and teaching, he feeds back into the closed loop and the entire process goes unchecked. The lesson is clear:

If nature isn’t providing the external feedback by eating you in a bunch of different ways, then you need to experience as many counterbalancing training perspectives as possible to replace the deficit. This is especially true in the contemporary individualistic western culture, since we have a fundamental distrust of time-honored institutions that by their very nature are designed to pass on static systems of knowledge that hold true across contexts.

Summary

So what does this all mean? How does this affect us? For some, quite strongly. Some instructors literally hang their guns up and turn in their badges, take their balls and go home. For those instructors that care about truth the question lingers: If clients can’t even tell if you are full of shit, then what’s the point?

What separates good material from bad material if your client is statistically an ignorant fool on the vast majority of anything ever? Why not just take the easy path, release something passable but not of a high quality, and rake in the cheddar? Most people will never even be in the position to use it for real, so why not? Seriously, why the hell not?

These are excellent questions that I have also grappled with, still do, and always will, with varying levels of motivation or depression. I came to the conclusion that it’s because as a coach, you are looking for transmitting truth, and so it’s the right thing to do. Period. You get it right, because it’s right, and you pass on the knowledge to the greater conversation of human experience. If you decide to specialize, then you are under an even greater responsibility to either broaden your own understanding by working with other coaches, or urge your client to do so.

One of my favorite movies of all time, “No Country for Old Men” summarizes this point astutely. In the film, Llewelyn Moss finds a suitcase of cash around a bunch of dead cartel members in the desert, with one of them being alive, but wounded. He takes the money, but then goes back to give water to the thirsty, dying man, and this is what arguably sets the entire movie chase into motion as he is discovered.

Chigurh, the main villain himself, takes a seemingly random approach to fate and death as he chooses whether his victims live or die based on the flip of a coin. Further, while Llewelyn pays for the sin of his kindness, the villain escapes in a car crash.

All throughout the movie, there is an upheaval of the popular causal notions of good deeds deserving good results and bad deeds deserving bad results. Many people watch the movie and think it is taking a standpoint of moral relativism and ambiguity, but I believe this can be read differently (see the footnoted quote and linked discussion). 1)“For Kant, virtue can’t exist in ‘the best of all possible worlds.’ That world, where virtue is always rewarded, is just a big Skinner Box. So, according to Kant, for virtue to exist in the world we need a failed theodicy, where the links between virtue and happiness cannot be guaranteed. Virtue, to be virtue, can have no guarantee. In short, virtue can only exist in a world like No Country for Old Men.Which is kind of a paradox. A film (and the world it conjures) that questions the value of virtue actually makes virtue come into existence. The failed theodicy of No Country helps virtue stand out all the more clearly. Despite their struggles and ultimate fates, we recognize Sheriff Bell and Carla Jean as virtuous people. And we recognize Chigurh as evil. The failed theodicy of No Country makes those recognitions possible. By contrast, the ‘virtue’ within, let’s say, a Disney movie, is just moralized self-interest. With a guaranteed ‘happy ever after’ we have the perfect theodicy, a world where virtue lawfully produces happiness. And all we can see in this “best of all possible worlds” (and Disney delivers on this score) is Homo economicus, self-interest disguised as virtue. Nothing in this sort of world is heroic or admirable. But virtue in No Country is the real deal, it’s the workaday heroism of doing the right thing simply because it is the right thing to do.” Richard Beck, “Theodicy and No Country for Old Men,” Experimental Theology, October 12, 2010, http://experimentaltheology.blogspot.com/2010/10/theodicy-and-no-country-for-old-men.html (accessed January 7, 2018).

In the end, doing the right thing needs to be its own reward. You do it because you must, and to question the effects or their supposed lack is “vanity.” The rain falls on the just and unjust alike, after all. Your clients may not know a damn thing. You may never see the person in the chain of life that is saved or affected by your teaching.

You could foist some fraudulent system on them, tell them it will make them a deadly ninja warrior, take their money and laugh all the way to the bank. You could even ignore the cognitive process, lie to yourself until you believe your own lie, and make the assumption that your material is probably effective. But then you’re not a coach. You’re certainly not a good coach.

Your clients may not know, but you will; and your conscience bites harder than any client ever could. If coaching is supposedly your life, you will, on your deathbed, know that you are a failure in your life’s work of pursuing the truth of violence.

My articles are often directly written about the very types of people that read them with a self-congratulatory nod that is devoid of any irony. I would ask you, the reader, to pause for a moment, and see if any of this applies to you. I can promise you it does to me, because after all, I am only human. But I am also a continual student, as must you be, lest you say you are a coach when you have long since abandoned the vocation.

References

| ↑1 | “For Kant, virtue can’t exist in ‘the best of all possible worlds.’ That world, where virtue is always rewarded, is just a big Skinner Box. So, according to Kant, for virtue to exist in the world we need a failed theodicy, where the links between virtue and happiness cannot be guaranteed. Virtue, to be virtue, can have no guarantee. In short, virtue can only exist in a world like No Country for Old Men.Which is kind of a paradox. A film (and the world it conjures) that questions the value of virtue actually makes virtue come into existence. The failed theodicy of No Country helps virtue stand out all the more clearly. Despite their struggles and ultimate fates, we recognize Sheriff Bell and Carla Jean as virtuous people. And we recognize Chigurh as evil. The failed theodicy of No Country makes those recognitions possible. By contrast, the ‘virtue’ within, let’s say, a Disney movie, is just moralized self-interest. With a guaranteed ‘happy ever after’ we have the perfect theodicy, a world where virtue lawfully produces happiness. And all we can see in this “best of all possible worlds” (and Disney delivers on this score) is Homo economicus, self-interest disguised as virtue. Nothing in this sort of world is heroic or admirable. But virtue in No Country is the real deal, it’s the workaday heroism of doing the right thing simply because it is the right thing to do.” Richard Beck, “Theodicy and No Country for Old Men,” Experimental Theology, October 12, 2010, http://experimentaltheology.blogspot.com/2010/10/theodicy-and-no-country-for-old-men.html (accessed January 7, 2018). |

|---|

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar