CQB Syntax & Adaptive Room Clearing

Borderland Nathan

Every instructor wants to have clients and trainees that can adapt on the fly in combat situations. I don’t know a single one that doesn’t, regardless of what they teach. In room entry, our fundamental techniques for different room types give a crash course in dealing with common complex “building blocks” we are likely to encounter. This is a good thing and it is like learning a new language, where the most common verbs and grammatical constructions are covered first, to help become functional as quickly as possible.

The State of the Art

In room entry, our complex building blocks are room layouts; we have center-fed and corner-fed rooms, named as such because that is where the door tends to be. We have L-shaped hallways, which in turn prepare us for intersections, and so on.

In language, we may have our chunks of grammar down, but this isn’t the same as syntax, which governs word order and how the sentence is contextually constructed. If bricks are the grammar of a wall, then the syntax is the mortar. Contemporary room entry and clearing techniques are still heavily “grammar-based,” and as a whole have not paid as much attention to the syntax of CQB.

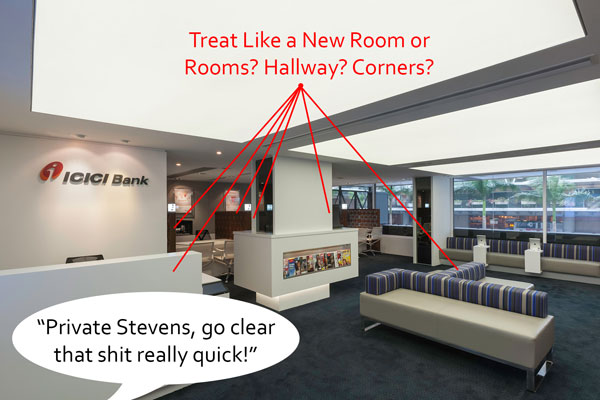

CQB syntax isn’t just our blocks of different room structures; it is all the rooms and human space connected, and how we enter some rooms in light of the whole. Some instructors may teach the wall flood for a center-fed room, for instance, but this technique only works on the barest base of center-fed rooms: No furniture, no secondary openings, no prepared resistance, no obstruction upon entry until the points of domination are achieved in the room, etc.

The Problem

How my team enters a center-fed room in the abstract, stripped away scenario is quite different from how I will enter a center-fed room where I can see partly inside prior to entry, and immediately determine that a “grammar-based” approach won’t work. More experienced teams eventually figure out their own approach to these situations, but it takes quite a bit of training to overcome the obstacles efficiently, and it presumes something that is patently false: That the abstract, empty, shoot-house center-fed room is the norm, with other situations being a deviation from that norm.

This may have been true in smaller town homes in places such as Iraq, where furniture consisted of a dirty blanket stretched across the floor, but in the vast majority of the real world those nice simple structures rarely exist. In fact, some countries in the East, for example, see space differently and organize their interior architecture nearly completely the opposite from western designs.1)See Edward Hall, The Hidden Dimension (New York: Anchor Books, 1990), 51-52. Not only does this cause issues inside the very room the team is entering, but it doesn’t even touch on how room entries change in light of other variables.

For instance, a center-fed room that contains a lot of furniture, threats, and visual or physical obstacles is no longer a center-fed room for practical purposes, because it cannot be cleared like one. Further, a center-fed room connected to a larger context is more than a center-fed room, and will be cleared differently. In complex systems terminology we would say that this room becomes an emergent situation in light of the larger context.

I may clear a room one way, but a room halfway down a hallway will be cleared differently than a room at the very end of a hallway. I have to adapt differently in light of the greater context of threat angles, compressed space, and team movement. We all know it, because we have all been in those situations. In the following video at the 11-second mark, a team enters and clears as though they are entering a center-fed room and they immediately experience cognitive overload, and part of the reason can be attributed to having the grammar but not the syntax in their method.

We all make concessions based on pros and cons as we see them in the moment, and try to adapt in the safest and most effective way possible. The reality is that many times this means sending a lower ranking private to do a quick slicing technique by himself that their own method would never allow in a more conventional scenario, with ironically the exact same parameters.

So what is the repeatable logic behind these adaptations; the adaptations that seem to be encountered more than the norm? That’s the nut we are trying to crack.

The key ingredient that is needed here is adaptive flow, and yet many of our room entry techniques cannot even handle a monkey wrench thrown into a regular entry. And even if a room entry is performed smoothly, there is always a pause after as the team is consolidated and prepares to push into the next. The more complex the context of the room, the longer the pause, and the longer the pause without action the more dangerous the situation. Even when this process is nailed down in training, it falls apart again as soon as you change the shoot-house layout, or increase intensity from dry fire to blanks, blanks to force-on-force, etc.

How Did This Problem Happen?

One answer can be found in current studies on human behavior in built environments. We often think of building types as determining human purpose and behavior within them in a top-down fashion, and in architectural terms we would call these buildings “fixed features.” In this viewpoint, a church building looks a certain way, a bank building looks another way and so on, with the building itself serving as a “fixed” cue for “semi-fixed” furniture and interior decorations within, which in turn cues proper “non-fixed” behavior.2)See Edward Hall, The Silent Language (New York: Anchor Books, 1990), and Amos Rapoport, The Meaning of the Built Environment: A Nonverbal Communication Approach (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990).

This may have been true in more traditional societies, where form and function mutually informed each other. To use a religious example, a Catholic church follows the form of an altar, with progressively holier places being higher off the ground and more restricted to public access. The fixed features themselves guide where the altar goes (semi-fixed), as well as who gets to behave (priest) and how (performing sacrifice). Contrast that with postmodern architectural style, however. A postmodern Catholic church is often difficult to even recognize as a Church, and the same can be said of many smaller denominational churches in places like a former basement or assembly building.

I don’t know whether to pray, or use it as a drug stash house

In an architectural style where the fixed features are more ambiguous, the semi-fixed cues such as the altar, the podium, and the decorations have to be more prominent to help guide behavior. Ultimately, semi-fixed cues guide human behavior more powerfully than fixed architectural cues, the only difference is that postmodern design needs more of them, and more obvious ones, to guide human behavior. If the building doesn’t tell me how to behave, then I need lots of signs, furniture, and other things within to guide how I act. To the frustration of many an architect, there are entire disciplines such as network flow theory and space syntax that have cropped up to study how human beings actually behave in the built environment, as opposed to the designer’s original intent.

This may sound overly academic, but is a very large aspect of modern Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, where ambiguous semi-fixed cues fail to give clear guidelines of social behavior, and leave the door open for anti-social and potentially criminal behavior. The purpose of CPTED is to have clearly defined, congruent fixed and semi-fixed cues that spur human guardians to take ownership over territory that is clearly “theirs.”

Now how does this apply to room clearing?

Most room clearing techniques still rely on a fixed-feature style that uses “points of domination.” One and two-man will take the corners, with three and four-man stepping to either side of the door for support, in one common example. The team follows this method regardless of the interior semi-fixed layout, and if they deviate from this method it is only as little as necessary before they return to the ideal team formation.

But if we take seriously the idea that semi-fixed features of the room are what guide behavior, why would this change for combat behavior inside the room? It certainly explains how room entries basically fall apart and turn into a reasonably common-sense, if not consistently effective, free-flow the second they encounter a deviation from the shoot-house norm. There are techniques, such as penetration methods that cross the center of the room, that try to take seriously the presence of semi-fixed feature such as furniture, which tends to be along the walls, and this is a step in the right direction. But this isn’t a universal feature of architectural styles, since we already discussed how other countries use space differently, and it still has to deal with the same issues of emergent context.

Solution

Clearly we need an updated approach. It can’t throw away all that is good in the old, anymore than we can expect to speak a language without grammar. But neither are we truly adapting to reality at our full potential if we try to speak a language with no syntax. Relying on a generic “ranger file” or “serpentine” formation any time we encounter complexity isn’t going to cut it. Any solution we develop needs to be principle-based, and take seriously at least two core aspects:

- Space as it is actually encountered.

- Human behavior as it actually occurs within space; by the team, the threat, and unknown contacts.

This is more abstract, and so in a sense it will have to be simpler. Rather than if-then rules for certain room configurations, it would have to use if-then rules for visual space in general. One example I use is that the only difference between a corner and a door is that a corner has one edge and a door has two, and so you would simply build off a one-edge clear when facing a door. This is a meta, or higher-level, principle that is able to be simply adapted in the moment, where a more traditional style would have to teach two different approaches entirely.

I can easily apply this “edge” method to anything that provides concealment and must be cleared: furniture, windows, a big pile of laundry, etc. It is heuristic, and treats space as it is actually encountered, as well as human behavior within it. People will tend to hide behind something whether it gives them actual cover or not, and that is because concealment is still objectively better than nothing at all. Again, semi-fixed space is still space, and space still guides behavior; good luck encountering every possible variation in training.

We need a new way.

References

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar