The Border Blood Network pt. 1: The Fatal Flaw

Nathan Wagar

The drug war has changed the face of violent crime in ways that we could never have expected. Unfortunately, regardless of how you feel about the ethics of the war itself, a lot of current policy has not kept up with the facts on the ground when it comes to facing the threat.

As a result, the Mexican government has not only increased the violence on its side of the border, but we have extended that violence across our own country because we have failed to take into account how criminal organizations actually function.

The first question you could ask, is whether this is even a serious issue? After all, most statistics show overall violence in the United States as going down, especially in places like California; this is why I will be focusing on the California effects in particular. When it comes to transnational cartel networks, as California goes, so goes the nation.

Mark Twain, among others, said that “There are three kinds of lies: Lies, damn lies, and statistics.” There is quite a bit of truth to that; statistics simply are, and they are true only to the degree that you use the proper method to explain a well-defined concept, and no further.

In California, overall crime has gone down, but the crime in specific places and of specific types has gone up, and as a direct result of new cartel influences.1)Kamala D. Harris, California Attorney General , Gangs Beyond Borders: California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime (March 2014). Since the majority of crime concentrates on the edges of high crime areas, people living in supposedly safer neighborhoods, but bordering these problem spots, will feel the effects of this new wave of violence.

At another time I will discuss how this is extending even into suburban neighborhoods. But why is this happening? To understand that, we need to rewind the tape and look at some basic systems concepts in this first article of the series.

System Type vs. System Structure

1. System Type

The two main kinds of systems are linear, and nonlinear. In linear systems, 1 + 1 = 2, the whole is equal to the sum of its parts, A → B → C in a causal chain, and all actions have an equal and opposite reaction. A lot of our traditional thinking is influence by these Newtonian concepts, and it leads us to believe that we can look at the parts of something and accurately predict the whole.

The problem is, we now know that nothing in the natural world is linear. Everything displays complex, sometimes chaotic behavior, and nothing is ever neat and tidy like Newton used in his examples. We can’t predict the weather, invading Iraq resulted in chaos, and research in quantum physics shows that the second we try to measure reality it has already changed and we’ve gotten our initial conditions wrong.

That isn’t to say that we can’t make predictions, but it is to say that we can only make very rough ones based on broad movements in time, and there is no guarantee that something will happen the same way twice. If you remember Malcolm in Jurassic Park, he gave an entire speech about this while discussing chaos theory. In this other type of system, 1 + 1 = 3. Small initial causes or actions may have completely disproportionate and unexpected results.

2. System Structure

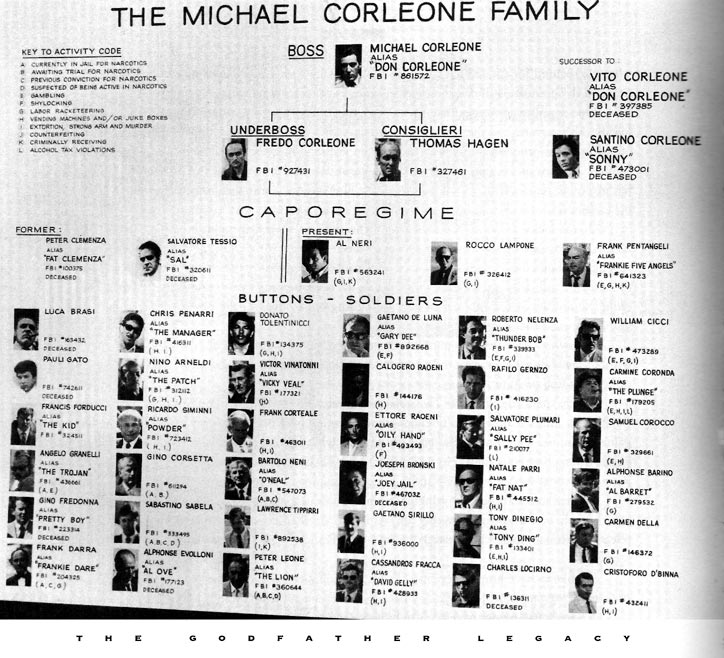

Most nonlinear systems in reality are complex, meaning they consist of many different interrelated parts, and these parts are organized in a hierarchy. When we think of hierarchies in crime groups we often picture La Cosa Nostra and the Five Families during Prohibition.

In this type of hierarchy there is a head boss, who has bosses under him, who has workers that in turn are bosses under them,2)Mette Eilstrup Sangiovanni and Calvert Jones, “Assessing the Dangers of Illicit Networks: Why al-Qaida May Be Less Threatening Than Many Think,” International Security 33, No. 2 (Fall 2008): 7–44. with information and decision-making flowing vertically up and down in one large bi-directional arrow. We can call this the “godfather model.”

“Godfather Model”

This is a valid way of picturing hierarchy, but it is not the only type. Depending on what the criminal organization is trying to do, different members may be connected in a “flat” network style hierarchy that doesn’t follow the vertical style. Rather than one large flow of information going up and down the chain, there are lots of little arrows cutting across levels depending on individual needs. We can call this the “Facebook model.”3)Juan Carlos Garzón, Mafia & Co.: The Criminal Networks in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia, trans. Kathy Ogyle (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2008), 24.

“Facebook Model”

Don’t Confuse the Two

The system structure is not the same as the system type. Unfortunately, viewing the world as a bunch of linear systems affects how you view structure. If I see everything as going in a straight line, I am more likely to force my view on the world because that’s the only frame of reference I have. When I’m holding a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

When you view a criminal organization in this way, the solution is to “cut off the head, and the body will die.” During Prohibition, law enforcement mapped out the Five Families as a vertical hierarchy, and focused on targeting the leading members of the hierarchy, always working upward to “cut off the head” in what they coined the “kingpin strategy.”4)Jason M. Lindo and Maria Padilla-Romo, “Kingpin Approaches to Fighting Crime and Community Violence: Evidence From Mexico’s Drug War,” Journal of Health Economics 58 (2018): 253-268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.02.002.

But most of us have seen the real-world consequences of this approach: targeting key leadership creates a power vacuum, causing more violence as the remaining criminals fight for control over the vacant position. This creates a “vacancy chain” that ripples downward, as each position that is filled creates a new opening that must be filled and so on, causing violence throughout the organization.5)H. Richard Friman, “Forging the Vacancy Chain: Law Enforcement Efforts and Mobility in Criminal Economies,” Crime, Law and Social Change 41, no. 1 (February, 2004): 53-77, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CRIS.0000015328.82955.f0.

Vacancy Chains

(Click To Enlarge)

(Click To Enlarge)

Step 1

Step 2

We now know that it is a myth that the Mafia ever had a rigid vertical structure,6)Joseph Albini, The American Mafia: Genesis of a Legend (New York: Appleton’s, Croft, 1971), and Alan Block, East Side-West Side: Organizing Crime in New York 1939-1959 (Swansea: Christopher Davis, 1979). but for the sake of argument let’s grant that it had more vertical structure than some criminal organizations. The main problem wasn’t so much that of structure, it was thinking of the Mafia with linear goggles. We knew the mob might adapt, but we thought we could predict how much.

We ended Prohibition and destroyed the overwhelming demand for what the Five Families offered, and so our kingpin strategy appeared successful by virtue of good timing. Applying this idea of vertical hierarchy and predictable effects to the war on drugs, however, has proved catastrophic, because with a different context we could see the glaring issues with the strategy itself.

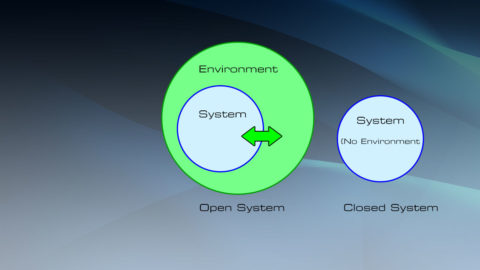

Context is the Key

We will discuss how these models come about, but the key detail is that neither one of these linear or flat models is “the” structure that a cartel will take. A complex adaptive system adapts to a larger environment. When its environment changes, its survival strategy changes, and its structure will change to make survival easier. The structure could be vertical, but it could also be flat/network-based, depending on what situation the cartel is facing.

In the next article we will discuss the criminal environment in Mexico, and how the cartels have evolved in response.

References

| ↑1 | Kamala D. Harris, California Attorney General , Gangs Beyond Borders: California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime (March 2014). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mette Eilstrup Sangiovanni and Calvert Jones, “Assessing the Dangers of Illicit Networks: Why al-Qaida May Be Less Threatening Than Many Think,” International Security 33, No. 2 (Fall 2008): 7–44. |

| ↑3 | Juan Carlos Garzón, Mafia & Co.: The Criminal Networks in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia, trans. Kathy Ogyle (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2008), 24. |

| ↑4 | Jason M. Lindo and Maria Padilla-Romo, “Kingpin Approaches to Fighting Crime and Community Violence: Evidence From Mexico’s Drug War,” Journal of Health Economics 58 (2018): 253-268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.02.002. |

| ↑5 | H. Richard Friman, “Forging the Vacancy Chain: Law Enforcement Efforts and Mobility in Criminal Economies,” Crime, Law and Social Change 41, no. 1 (February, 2004): 53-77, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CRIS.0000015328.82955.f0. |

| ↑6 | Joseph Albini, The American Mafia: Genesis of a Legend (New York: Appleton’s, Croft, 1971), and Alan Block, East Side-West Side: Organizing Crime in New York 1939-1959 (Swansea: Christopher Davis, 1979). |

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar