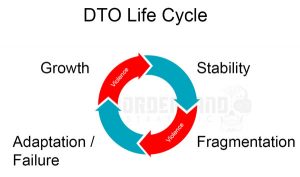

Nathan Wagar A current fad in the tactical community is to speak knowingly about the drug violence in Mexico as though it is a sandstorm of decapitations and terrorism that will blow over the border and sweep across American streets, all being shot-called by some laughing brown guy in purple ostrich boots in Juárez. I have to chuckle, at least a bit. Most of these people don’t live on the border, don’t visit Mexico, don’t have family in Mexico, and don’t even speak Spanish well enough to order a taco from somebody that isn’t named Chad. You Know Who You Are Even those in military special operations teams have very strong opinions about the issue that cause them to make serious errors when discussing how to solve the problem. This is a case of expertise bias: Men that have a lot of experience with insurgencies that use a certain brand of violence see similar violence, but in a completely different context, yet still infer a similar cause. But drug cartels are not insurgencies, and while some of the more recent violence seems similar, Mexico is not the Middle East. It has its own history, its own dynamic that is inseparable from the United States, and treating one like the other is catastrophic for all parties. I will discuss why they are not insurgencies in more depth in another article, but in this one I will focus on some basic adaptive systems concepts to explain why these drug cartels are not going to be bringing a wave of bloodshed across the border and into the states; at least not in the way that many people think. Not a “Cartel” The first thing to keep in mind is that the word “cartel” is a misnomer, since the cartels don’t have the amount of control they did in past times, and never really did.1)Carmen Boullosa and Mike Wallace, A Narco History: How the United States and Mexico Jointly Created the “Mexican Drug War” (New York: OR Books, 2014), 77-78. This is why most closed and open-source academic literature on the subject refers to them more properly as “drug-trafficking organizations,” or DTOs, which I will refer to them as from here onward for consistency’s sake. Rather than thinking of them as insurgencies, we should think of them as aggressive franchises that supply a product. They overlap with, meld with, and in specific contexts even supplant the State, but only in the pursuit of profit margins. This is critical: The end goal is money, not State control. State control can overlap but is incidental to the pursuit of their control of the drug market.2)Shawn Teresa Flanigan, “Terrorists Next Door? A Comparison of Mexican Drug Cartels and Middle Eastern Terrorist Organizations,” Terrorism and Political Violence, 24 (2012), DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2011.648351. Organizations and Control Recently businesses have applied complex adaptive systems science to explaining businesses as growing organisms. These same ideas help explain the growth and demise of not just individual DTOs but also the drug market as a whole. A key idea when dealing with an adaptive system, is that they have to have internal control and maintain a dynamic equilibrium, like your body maintaining a temperature of roughly 98.6 degrees, or else they fall apart. In a DTO, they will have a different slice of the drug pie depending on where they are located in Mexico, how many foot soldiers they have, what their skill sets are, and so on. Not all DTOs are created equal, and their business models and structures will change depending on their particular strengths. In any adaptive system, there is a sphere of activity but also a sphere of control. The goal in a system is to have the two perfectly overlap in what we call a “control balance.” The Roman empire fell when it’s reach exceeded its grasp, and outlying settlements no longer had the strong military control to efficiently send flows of resources and information, and so it crumbled. Likewise, anybody that has tried to give and execute orders when there are too many conflicting leaders in the room, knows how much chaos can be involved. If a DTO has tons of product but not enough workers, then it doesn’t have control as a system, it can’t reach a dynamic equilibrium, and it has to either make cutbacks or it will fail. This situation could happen in different ways. A DTO could have 10 people in a very tight territory in Mexico and way too many resources to control it all, or it could have 50 members stretched across too large of a territory. Either way, there has to be a balance between resources, members, and territory. Having too much product to deal is practically speaking the same as too little product to deal. In systems terms, these cases of either too little information, or too much, both fall under the same concept of organizational entropy. As an adaptive system, when a DTO experiences entropy, it can either adapt by diversifying, fragment into smaller functioning DTOs, or fail entirely. Fragmentation & Memory All the larger DTOs like those affiliated with Sinaloa have eventually experienced entropy and fragmented. In fact, we don’t even know how many DTOs there are, although the most recent count put it somewhere at over 45.3)“Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” Congressional Research Service (December 20, 2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov R41576. The rise in violence is due to a combination of larger and smaller DTOs, all in a state of territorial flux, with boundaries criss-crossing all over Mexico. In order to reestablish control, DTOs take several different strategies. Sinaloa still has a lot of old-school influence, in the sense that they have one of the oldest “organizational memories.” Not every DTO can cook product, handle the logistics, and provide foot soldiers. Only the ones that have the resources on a large scale can handle these large operations, and this requires a system “memory” that has all this knowledge and lessons-learned institutionalized over time. Because of this, we can expect to see the influence of Sinaloa-based DTOs over large swaths of Mexico from South to North, handling all aspects of the drug market, and indeed that is exactly what we observe. The Zetas, by contrast, have a relatively short “system memory,” since they began as the muscle for the Gulf cartel. They bit off more than they could chew and have had to diversify out of the drug market exclusively and rely more on extortion and “toll-booth” operations on the border.4)Antonio L. Mazzitelli, “Mexican Cartels’ Influence in Central America,” Western Hemisphere Security Analysis Center, 45 (2011), http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/whemsac/45. We will see this pattern play out regularly, where DTO size and function predicts where we will see it move to in Mexico, and what operations it will focus on. Smaller DTOs will generally move to geographic drug market “choke points” or “control nodes” that provide a large amount of system bang with minimal effort.5)María del Pilar Fuerte Celis, Enrique Pérez Lujan and Rodrigo Cordova Ponce, “Organized Crime, Violence, and Territorial Dispute in Mexico (2007–2011),” Trends in Organized Crime (2018): 1-22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-018-9341-z. Some focus on the border and may handle human trafficking, others, like those in Michoacán, focus on very specific resources normally handled by the State, such as iron ore exports.6)E. Eduardo Castillo, “Mexican Drug Cartels Are Becoming Diversified ‘Multinational Corporations’” Associated Press, March 17, 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/mexico-drug-cartel-makes-more-dealing-iron-ore-2014-3, (last accessed February 26, 2020). There are at least four different types of “DTO” according to their function in the illegal market.7)Eduardo Guerrero-Gutiérrez, “Security, Drugs, and Violence in Mexico: A Survey,” 7th North American Forum, Washington, DC, 2011. Gridlock Right now the DTOs are in a state of tenacious economic gridlock. The worst violence happens when you have a power vacuum, where there are several equal cartels, and one or more is suddenly more powerful because another loses power, typically due to military intervention.8)Javier Osorio, “The Contagion of Drug Violence: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Mexican War on Drugs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution (2015), DOI: 10.1177/002200271558704. This violence will be concentrated specifically along those boundaries as they shift and one group tries to reestablish control, but violence dies down in areas where all the DTOs are roughly equal in power and size. And therein lies the problem: How does a small DTO sustain itself without organizational memory, or ability to extend its physical territory? Outsourcing. Diversification & Outsourcing Fentanyl was a game-changer for DTOs. It allowed small criminal groups with hardly more organizational memory than a typical street gang to reap respectable profits on a small amount of product. This let criminal groups remain resilient that normally never should have been able to survive in the drug market.9)Elyssa Pachico , “Re-emergence of Splinter Criminal Group is Bad Sign for Mexico,” InSight Crime, September 10, 2012, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/guerrero-gang-mexico-cartel-fragments/, (accessed February 26, 2020). But that still leaves the problem of moving the product when your criminal group can’t actually move safely across a fractured criminal landscape. Further, moving drugs is expensive, and it gets more expensive the farther North you have to move them. As an example, the price of product can increase 63% just by making a short hop over the border from Juárez to El Paso.10)Howard Campbell, Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juárez (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 122. Enemy territory provides friction, and friction lowers profit. A functional government and law enforcement such as found in the US provides friction, and again, friction lowers profit. Even when offsetting costs by using fentanyl to lace the product, this could have been a death blow for the contemporary small-time DTO. Enter the United States, stage left. The United States has a well established relationship and history with Mexico, that has also resulted in an equally well established Chicano street and prison gang culture from both legal and illegal immigration. What I don’t think many people seem to understand is how powerful our gang culture actually is. The DTOs in Mexico have always had a friendly relationship with, say, the southern California prison gang La Eme, but when their illegal members get sent to California prisons, they have to pay to have their sicarios protected, the same as anyone else. The recent hysteria with MS-13, is actually the result of Los Angeles street gang members that were illegal, got deported, and exported our gang culture to Salvadorean prisons, bringing a level of organization to the prison gangs there that had never existed beforehand.11)Benjamin Lessing, “Logics of Violence in Criminal War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 8 (2015): 1486-1516, DOI: 10.1177/0022002715587100 jcr.sagepub.com. And even with this newfound organization, MS-13 can’t break into the drug trade.12)“MS-13 in the Americas How the World’s Most Notorious Gang Defies Logic, Resists Destruction,” InSight Crime and CLALS. That’s why most of the cases in the United States of MS-13 are either standard street gang fare, or vicious teenager-on-teenager murders by illegals that are knowingly trying to get the attention of Salvadorean prison gangs when they get deported, in order to “earn their stripes” before their inevitable arrival in Central American prisons. But, and this is critical, the actual organized MS-13 presence is relegated to stay deep in Central America. The US gang culture is too powerful up North, the Mexican DTOs are too dominant down South, and MS-13 has had to predictably either focus on extortion and muscle along the border for the DTOs in roles similar to street gangs like Barrio Azteca, or diversify out of the market and provide muscle for transnational crime.13)Gangs Beyond Borders: California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime, March, 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General, 31. The Border Relationship So what does this outsourcing entail for border movement? I mentioned that certain DTOs like Sinaloa have long-standing relationships with specific prison and street gangs in the United States. But these relationships are ones of mutual benefit, not ones of control exercised from Mexico. One way in which Mexican drug violence has added to violence in our country is indirectly. Since so many DTOs in Mexico have fragmented, having just one customer no longer provides enough profit. The map has changed so many times that some DTOs now move product to multiple competing street gangs in the United States, and in the case of California this means violence that stretches across the state as northern gangs now have to extend their control down South into enemy territory, to move product from the border. But the border is not really to be crossed; it is to be used. Vehicles from up North are stolen and then moved down South to Mexico to use in hits since the VIN numbers don’t register in the system. Likewise, US gang members often receive lists from DTOs, kidnap people up North, then dump them down in Mexico where they can be killed, since a body is just another body over there. Street gang members with citizenship also have the ability to cross the border and traffic it over themselves, absorbing the cost on their end with higher street prices, distributing to a market in the US that they understand intimately. The media knowingly manipulates this far more complex dynamic; they may refer to stateside killings as being done by “sicarios” or “cartel killers,” when the reality is they are merely US street gang members performing a freelance service in a place that the DTO doesn’t have the influence to touch directly.14)See for instance, how an American citizen residing in Albuquerque is referred to as a “cartel hitman” in Jaimie Veleta, “Alleged Mexican Cartel Hitman Sentenced for 2008 Murder” KRQE Media (Jan 3, 2020) https://www.krqe.com/news/crime/alleged-mexican-cartel-hitman-sentenced-for-2008-murder/, (accessed February 26, 2020). Likewise, 28 criminals are referred to as “cartel operatives,” even though 26 of them were US residents and gang members, and only two members were Mexican nationals, see “Feds: Drug Bust Nets 28 Cartel Operatives,” Albuquerque Journal (April 28, 2017) https://www.abqjournal.com/995396/feds-drug-bust-nets-28-cartel-operatives.html, (accessed February 26, 2020). They perform the hit because it profits them, otherwise they wouldn’t, and the DTO would try to hire someone else. This is less a case of a Mexican shot-caller and more that of a new, emerging criminal “dark network” that transcends boundaries altogether. When you do see a “cartel operation,” it is nearly always a very small cell of up to three illegals that set up a base of operations, often a trafficking stash house, specifically because they have the cooperation of a local street gang. The street gangs provide the muscle and logistics because illegal immigration provides a market of vulnerable, largely invisible people to be exploited apart from the legal system. The DTO cells in the states can’t operate on any large level because they don’t have the power due to entropy, and if they get arrested they just get deported back to Mexico, instead of continuing their influence in prison like a US street gang member would. Their illegal status, whether working for the DTOs or being exploited by them, is what gives the DTO power over them. The legal status of the US gang members prevents them from being sent to a Mexican prison. Corruption and State-level Violence A final note regards some of the more spectacular instances of violence that we see against government forces in Mexico, such as the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación DTO shooting down a helicopter. Mexican government is complex, and we do not have any parallel in the United States to their corruption issue. This is the topic for another article entirely, but I will say one thing in light of the previous systems concepts. An adaptive system naturally goes through a cycle of growth, stabilization, fragmentation, and then adaptation or failure. In a criminal system, the most violence happens during periods of growth and fragmentation.15)Brian D. Fath, Carly A. Dean, and Harald Katzmair, “Navigating the Adaptive Cycle: An Approach to Managing the Resilience of Social Systems,” Ecology and Society 20, no. 2 (June, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07467-200224. Only a larger DTO, or one with long-term regional power such as existed at one time in Michoacán, has the organizational memory, resources, and relationship with the government to execute that kind of organized violence. But the ones that do, like the Zetas, tend not to last long, since they burn too brightly for the State to allow them to exist.16)Christopher Woody, “Mexico Says it Caught Gunmen who Shot Down an Army Helicopter — and it May Signal Trouble for the Country’s Most Powerful Cartel,” Business Insider, August 2, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/mexico-catch-cjng-jalisco-cartel-gunmen-who-shot-down-army-helicopter-2018-8 (accessed Feburary 26, 2020). Larger, sustained, more successful DTOs stabilize into relative peace with the State in order to continue making money. The more violent DTOs, if they continue to exist, stay small and do not have the resources or influence to carry on up North. Friction still affects profit. The DTOs that do have the power to fight the State ironically reach a level of dynamic equilibrium and become more peaceful for profit. Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, or CJNG, is a new fragment off the larger Sinaloa, so it has all the violence associated with a newer, smaller, DTO, but a good deal of organizational memory, resources, and size from longstanding Sinaloa ties as well. But for it to remain a player in the long run, it will have to stabilize or eventually fragment again, and indeed it already has fragmented.17)Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG),” InSight Crime, May 21, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/mexico-organized-crime-news/jalisco-cartel-new-generation/, (accessed February 26, 2020). This could have been expected, since there is too much territorial competition for the growth stage to take place in the current drug market. The new fears about it being so violent while also being relatively large are valid, but necessarily temporary. Summary Does the situation in Mexico threaten to spill into bloodshed in the US? Yes and no. Yes in the sense that a changing map of relationships is spreading crime across countries in unique ways, but no in the sense of Mexican death squads crossing our borders and executing our citizens at will as they do in Mexico. Mexico’s history of government corruption, the fragmentation of the DTO landscape, our gang and law enforcement culture, government, and basic truths about how businesses operate, prevent this from happening. The drug market is no longer the drug market. DTOs are not only fighting for slices of the same pie but also different pies, and there is no putting Humpty Dumpty back together again. The new reality is a mosaic of small, tightly focused criminal groups that network and outsource across markets and borders. Will the Mexican Cartel Wars Come North?

References

| ↑1 | Carmen Boullosa and Mike Wallace, A Narco History: How the United States and Mexico Jointly Created the “Mexican Drug War” (New York: OR Books, 2014), 77-78. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Shawn Teresa Flanigan, “Terrorists Next Door? A Comparison of Mexican Drug Cartels and Middle Eastern Terrorist Organizations,” Terrorism and Political Violence, 24 (2012), DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2011.648351. |

| ↑3 | “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” Congressional Research Service (December 20, 2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov R41576. |

| ↑4 | Antonio L. Mazzitelli, “Mexican Cartels’ Influence in Central America,” Western Hemisphere Security Analysis Center, 45 (2011), http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/whemsac/45. |

| ↑5 | María del Pilar Fuerte Celis, Enrique Pérez Lujan and Rodrigo Cordova Ponce, “Organized Crime, Violence, and Territorial Dispute in Mexico (2007–2011),” Trends in Organized Crime (2018): 1-22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-018-9341-z. |

| ↑6 | E. Eduardo Castillo, “Mexican Drug Cartels Are Becoming Diversified ‘Multinational Corporations’” Associated Press, March 17, 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/mexico-drug-cartel-makes-more-dealing-iron-ore-2014-3, (last accessed February 26, 2020). |

| ↑7 | Eduardo Guerrero-Gutiérrez, “Security, Drugs, and Violence in Mexico: A Survey,” 7th North American Forum, Washington, DC, 2011. |

| ↑8 | Javier Osorio, “The Contagion of Drug Violence: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Mexican War on Drugs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution (2015), DOI: 10.1177/002200271558704. |

| ↑9 | Elyssa Pachico , “Re-emergence of Splinter Criminal Group is Bad Sign for Mexico,” InSight Crime, September 10, 2012, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/guerrero-gang-mexico-cartel-fragments/, (accessed February 26, 2020). |

| ↑10 | Howard Campbell, Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juárez (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 122. |

| ↑11 | Benjamin Lessing, “Logics of Violence in Criminal War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 8 (2015): 1486-1516, DOI: 10.1177/0022002715587100 jcr.sagepub.com. |

| ↑12 | “MS-13 in the Americas How the World’s Most Notorious Gang Defies Logic, Resists Destruction,” InSight Crime and CLALS. |

| ↑13 | Gangs Beyond Borders: California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime, March, 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General, 31. |

| ↑14 | See for instance, how an American citizen residing in Albuquerque is referred to as a “cartel hitman” in Jaimie Veleta, “Alleged Mexican Cartel Hitman Sentenced for 2008 Murder” KRQE Media (Jan 3, 2020) https://www.krqe.com/news/crime/alleged-mexican-cartel-hitman-sentenced-for-2008-murder/, (accessed February 26, 2020). Likewise, 28 criminals are referred to as “cartel operatives,” even though 26 of them were US residents and gang members, and only two members were Mexican nationals, see “Feds: Drug Bust Nets 28 Cartel Operatives,” Albuquerque Journal (April 28, 2017) https://www.abqjournal.com/995396/feds-drug-bust-nets-28-cartel-operatives.html, (accessed February 26, 2020). |

| ↑15 | Brian D. Fath, Carly A. Dean, and Harald Katzmair, “Navigating the Adaptive Cycle: An Approach to Managing the Resilience of Social Systems,” Ecology and Society 20, no. 2 (June, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07467-200224. |

| ↑16 | Christopher Woody, “Mexico Says it Caught Gunmen who Shot Down an Army Helicopter — and it May Signal Trouble for the Country’s Most Powerful Cartel,” Business Insider, August 2, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/mexico-catch-cjng-jalisco-cartel-gunmen-who-shot-down-army-helicopter-2018-8 (accessed Feburary 26, 2020). |

| ↑17 | Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG),” InSight Crime, May 21, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/mexico-organized-crime-news/jalisco-cartel-new-generation/, (accessed February 26, 2020). |

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar