CQB Syntax: One-Man vs. Team Tactics

Nathan Wagar

I have covered the topic of CQB syntax elsewhere, but let’s give a brief summary.

- Space Syntax is based on movement and visual sight in space.

- Space Syntax originally comes from complexity and graph theory, and was applied to architecture.

- We are applying some basics to analyze CQB, and we refer to it as “CQB Syntax.”

In CQB, there are two different kinds of domination because of the unique addition of firearms to human combat: Visual, and physical. I can always see more than I can physically control. Visual dominance is fine in some situations such as an extremely relaxed ROE where I can shoot someone on sight, when I am just passing through an area to go to the more immediate target location, or providing intelligence, but this is less helpful in any situation where I run the risk of going hands-on with a contact.

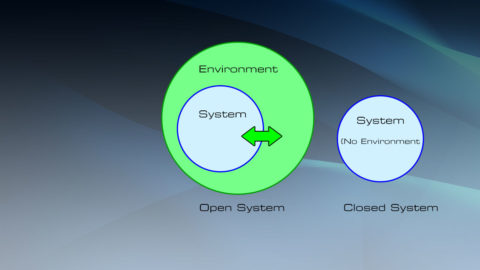

Physical dominance includes visual dominance, but it more directly puts you in a position to control the actual space that a threat can move through. In architecture, these control points are treated specially since they affect crowd flow, security, and a host of other factors. In CQB, they become important for truly owning the battlespace. In graph theory, these control points are called “nodes,” and this theory has many applications, as you can see here, for example:

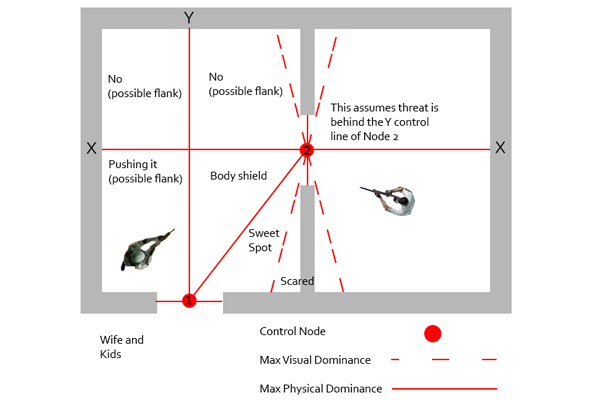

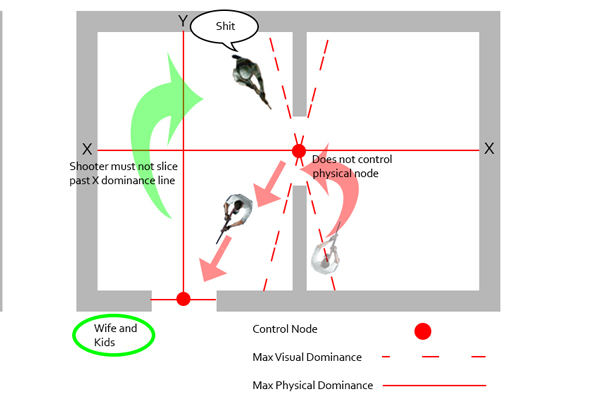

For our purposes, we treat every threshold space as a line with a halfway point. In single-man clearing especially, we focus on controlling the thresholds rather than the space in the room in the same way as with team-based clearing. This is because we need to use the structure of the building to prevent multiple threats from triangulating on us. To control a space, I need to be able to cut off the threat before he can move past a control node into already-cleared space. I have to be close enough to do this throughout my visual clear of an edge. Regardless of how I slice, I need to physically converge on a syntax point the closer I get to the edge I am clearing, staying in the “sweet spot” not just on the approach, but through the entire clear until the space to the near side of the syntax line is clear, as in Ex. 1 below.

Ex. 1

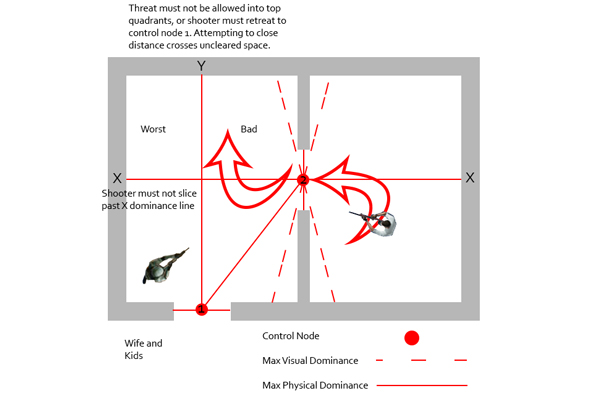

If there are multiple control nodes, then if a threat passes, say, node 2 in the example below, I need to converge or even retreat to node 1 to regain some form of dominance and protect previously cleared space. I cannot risk a flank or crossfire scenario (See Ex. 2).

Ex. 2

The difference between visual and physical dominance seems obvious, but treating it seriously will change how you do the simplest CQB techniques. Take slicing a corner, for instance. Most instructors teach to perform a slice with varying levels of precision. The fact is, all the different options are along a spectrum. The farther away from the corner you are, or the harder the angle you take, the more visual dominance you have, but the slower your slice and the more potential lateral threat movement you have to deal with. Less of you is exposed, but if the space isn’t compressed, you may lose physical dominance.

Physical dominance places you closer to the edge and typically in a better position to control the physical control point of the room, and it is also faster. Sometimes it is too fast, allowing you to slice chunks of the room more quickly than you can respond to a sudden threat inside, who can see part of you just as or even before you can see him. There are other downsides as well, just as there are other upsides. These options I have just mentioned apply before the threat has seen you; in a post-contact situation, being close to or farther away from the corner carries different pros and cons for manipulating the battlespace to your benefit.

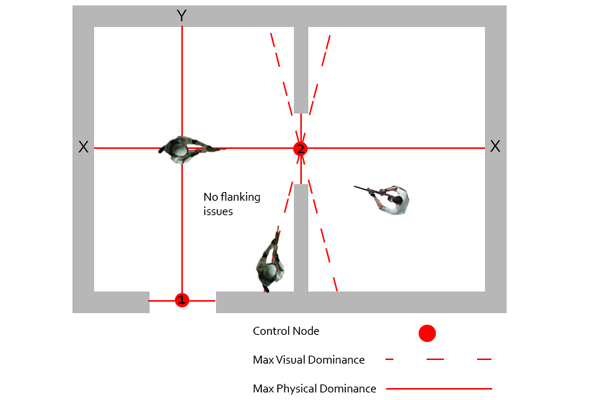

Most team-based CQB takes advantage of multiple team members to own both visual and physical space, maximizing angles to easily get the first shot as well as put hands on a threat (See Ex. 3). In tactical teams, we get so used to this advantage that we take it for granted, and this is disastrous when we apply it to single-shooter CQB. Suddenly we need to be Nazis about those fundamentals that “everyone knows,” and our sliding spectra have to shift in accordance with our new concerns.

Ex. 3

There is far too much to cover in just an article, but let’s take a look at how some very common variations seem effective enough, but can actually fail, and fail hard, when we take physical combat into account.

Example 1 – Slicing to the far side of the door:

This technique is everywhere; a single shooter slices the door, moving from the near side to the far side to clear a majority of the room from outside the door, before dealing with the final uncleared slices in any number of ways. One major problem with this technique I discuss here:

The basic idea is that treating the room as an abstract space instead of a space where a threat can move in real time can cause you to enter into a “visual ambush” of your own making. I suggest reading the article for a more in-depth discussion. Another problem is that moving to the far side of the door allows your barrel to be seen from the near side of the door.

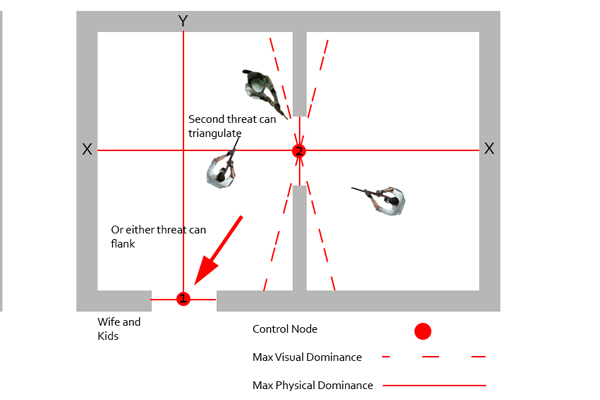

More specific to this article’s topic, however, we have an added problem. Slicing to the far side of the door maximizes visual dominance but cedes physical dominance. It isn’t hard to see why this is a major problem for a single shooter; in a tactical context I can get flanked and have multiple threats triangulate on my position. Barring a massive training advantage, I lose. (See Ex. 4)

Ex. 4

But the majority of single shooter situations will be in your own home, most likely protecting a loved one. What happens if a threat runs out of the room as you are clearing and makes it to your child, who may or may not have stayed exactly where you told him to? Shooting the threat is no guarantee, criminals generally do the same thing after they get shot as they did before, until they bleed out. If you aren’t controlling the physical node of the space, then there is a greater than equal chance that the threat can get there before you, and even worse you may find yourself in a crossfire situation (See Ex. 5).

Ex. 5

I present a solution to just this scenario in what I and others advocate as a corkscrew style slice, that clears from the near edge of the door, and remains facing not only uncleared space, but also controls the physical dominance node. To many people, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and this is true, but not in every context. You can listen to this podcast for a discussion on this type of slicing:

Example 2 – Running the rabbit into the room:

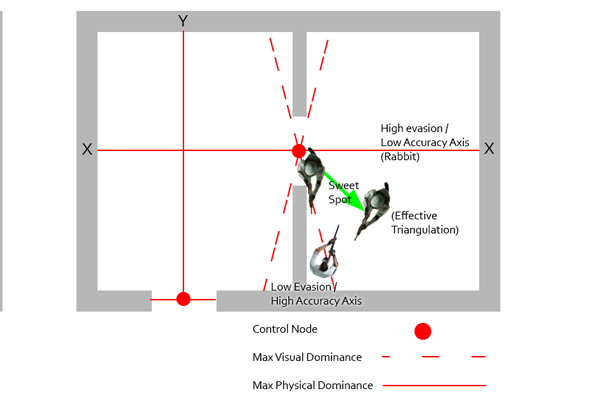

This is another excellent technique, with several qualifications; that nevertheless is a risky game for a single-shooter style of clearing. In this technique, a team clears a majority of the room from outside the door, then enters and triangulates on the final slice where a threat may be hiding, with the first man entering far across the room and the second man snapping or firing from the door frame. There is another sliding scale to this technique; it was originally called running the rabbit, because the first man was drawing fire at a hard 90, but was unable to accurately engage the threat.

The focus was on the second shooter engaging a distracted threat from the door frame, with one-man “taking it for the team.” This technique can still be successful, but fails to take advantage of the very things that make it so powerful. Again, there is a sliding scale depending on what we want to accomplish: if the one-man goes straight for the threat along the near wall, he has maximum accuracy but minimum evasiveness.

If the one-man goes at a hard 90 across the room as in the traditional rabbit technique, he has maximum speed for evasiveness but minimum ability for accurate shots. The only way to compensate for this loss of accuracy is to slow down and lose reaction speed in firing the first shot.1)J. Pete Blair and M. Hunter Martaindale, Evaluating Police Tactics: An Empirical Assessment of Room Entry Techniques (Oxford: Elsevier Inc., 2014), 57-58 If we view this as a spectrum, it shouldn’t be hard to see the compromise: a 45 degree entry gives the best of both worlds. The one-man’s entry leads the eye away from the door frame, and also allows both shooters to triangulate and engage on the threat before he can properly react (See Ex. 6). This theory was tested over several years with multiple teams of varying experience levels and proven empirically.2)Ibid., 67-68.

Ex. 6: Split Entry

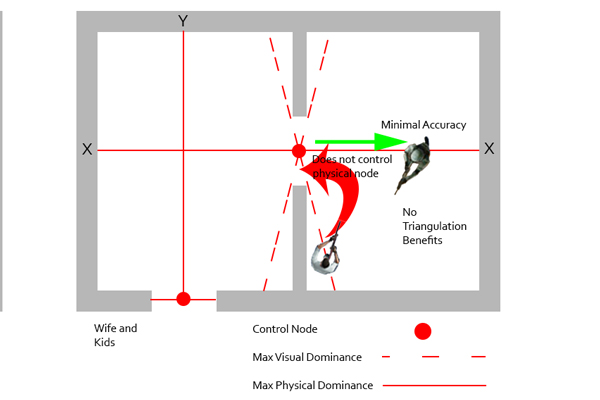

So far so good. But this extremely effective technique is less effective for a single shooter, for the same reasons as the far-side slice. If I slice the majority of the room from outside the door but then enter across the room to surprise the threat with lateral movement, I lose the physical control node. I achieve maximum visual dominance but may even lose actual accuracy as well as the physical flow of the room (See Ex. 7).

Ex. 7

This changes depending on the size of the room and other contextual factors. If the room is quite small, or I adjust my angle, then I may still be able to control the physical node by cutting off his path in motion, as well as getting visual dominance and the element of surprise. Conversely, if the room is that compressed, I am also easier to shoot. This is a viable technique that is taught by some very popular instructors, but ironically they are applying the technique improperly in a single-shooter scenario by virtue of taking the fundamentals for granted. See this clip for example, of an instructor demonstrating a violation of the floating angle at 0:13, as well as CQB syntax at 0:21:

Conclusion

There are many more examples, but these should suffice for now. Even basic CQB syntax drastically effects our technique, and suddenly small “variations” carry massive consequences. This is one of the dangers of having an instructor with tactical experience teaching those same tactics within an individual shooter context. This is not to say that we need to keep all these angles and theories in mind, this would be ridiculously complex. However, it does mean that if we are going to instruct or learn from an instructor, we need to make sure that the techniques themselves are relentlessly consistent with good fundamentals, and have been worked out well beforehand.

How did many of these errors happen? Paper targets, and overly-controlled force-on-force. Allow a threat to fight, stay alive a bit longer after he is shot, or rush out of the room according to the dictates of his own conscience rather than patiently waiting in an uncleared space, and suddenly you will appreciate the necessity for strong physical dominance.

Make the necessary tweaks, and watch your ability to adapt to new contexts in training increase tenfold.

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar